ATTACK FROM THE AIR

Air Raids

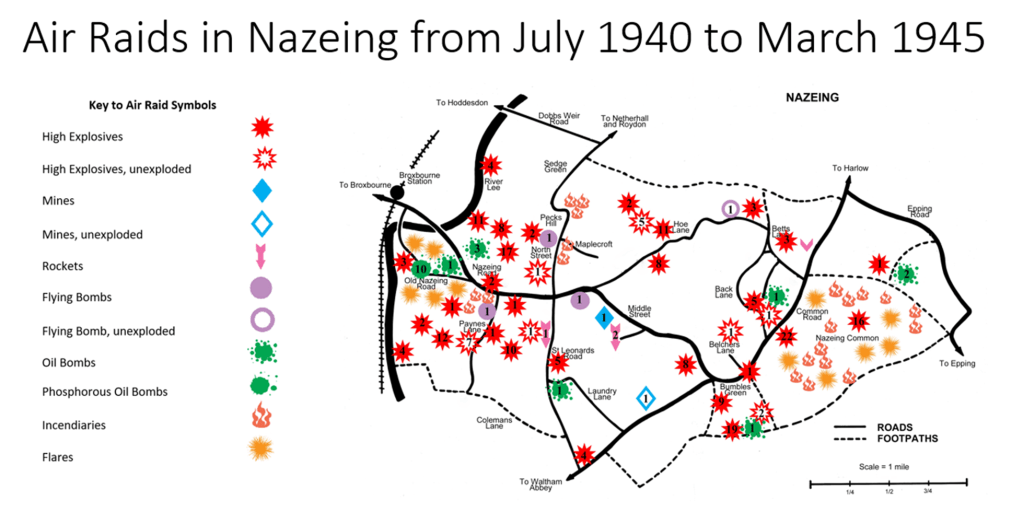

The first record of bombs landing in Nazeing was on the 26th July 1940. The senior Air Raid Warden, Mr Archer, gave his records to the vicar, The Rev Sutherland, to include in the History of Nazeing booklet that was published in 1950. The records show that a total of 244 bombs and numerous incendiaries fell on the village between July 1940 and March 1945. Many Nazeing residents at the time thought this number was an underestimate!

The first air raid resulted in two high explosives landing in the St Leonards Road area. It obviously created lots of interest resulting in this photo.

From left to right: Bert Brown, Jim Crowe, Sid Myson, ? , Dusty Brace, ? , ? , Kath Brett, Wally Bayford, John Welch, and in the crater Robin Pallett. We will meet Robin later in our story of Nazeing at War.

The Battle of Britain took place from July to October in 1940 over southern England after the fall of France to the Germans. Many Nazeing residents remember watching the dog fights over head. Until that time, for most people the war must have felt a long way away from the village.

This map, by Jennifer Andrews, was produced from the information recorded by the vicar, It shows us where the bombs landed and what type they were.

Nazeing Common was under attack mainly during the latter part of 1940 (September, October, November and December) with the exception of a rocket near the Sun Inn during March 1945 which we will hear about later on. Forty high explosives and numerous incendiaries, too many to count, were recorded landing on the common and surrounding area. This probably illustrates that the dummy airfield did fool the enemy for a short time at least.

Lower Nazeing, the area of the village with numerous glasshouses and important for food production, appears to have been targeted throughout the duration of the war. An intense period of air raids culminated with 10 high explosives on Chapmans Farm and St Leonards Road on 30 January 1941.

The villagers did get some respite with no bombs or rockets from May 1941 until February 1944 when the war was being actively fought on the eastern front and in North Africa. There was one exception. On the 7th September 1942, for just one day, flares were dropped in very large numbers both in Lower Nazeing and on the Common. Following the allied invasion of Italy in January 1944 the air raids recommenced with high explosives, incendiaries and phosphorous bombs. After D Day on June 6th, when the allied forces landed on the Normandy beaches in France, the flying bombs started to arrive. These were known as doodle bugs. Every land girl or farm hand knew as long as they could hear them, they were safe. If the engine stopped then you needed to jump into a ditch for shelter. The rockets followed; you couldn’t hear them coming. The first of four that dropped on the village landed in St Leonards Road on the morning of Sunday 12th November.

Air Raid Shelters

There were two air raid shelter in the garden of the Old School House, Bumbles Green, used by the school children from 1940 to 1945. One of these also housed the controls for the air raid attack warning siren which was erected on two poles next to the shelter, and could be seen from Welch’s garage forecourt. After the war it was still connected to the main area control at Fylingdales, Yorkshire – known as the four minute early warning system. It was decommissioned in 1993. The shelter became unsafe and was demolished in 1995.

This photo below shows one of the air raid shelters in the garden behind Bumbles Green School. The anti-tank ditch also ran behind the school. Michael Hills, known as Boke, the son of the headmaster Marcus Hill, is seen with his wife, Ann, their dog and friend’s children, probably in 1954.

Boke and Ann Hills in the garden at Bumbles Green School.

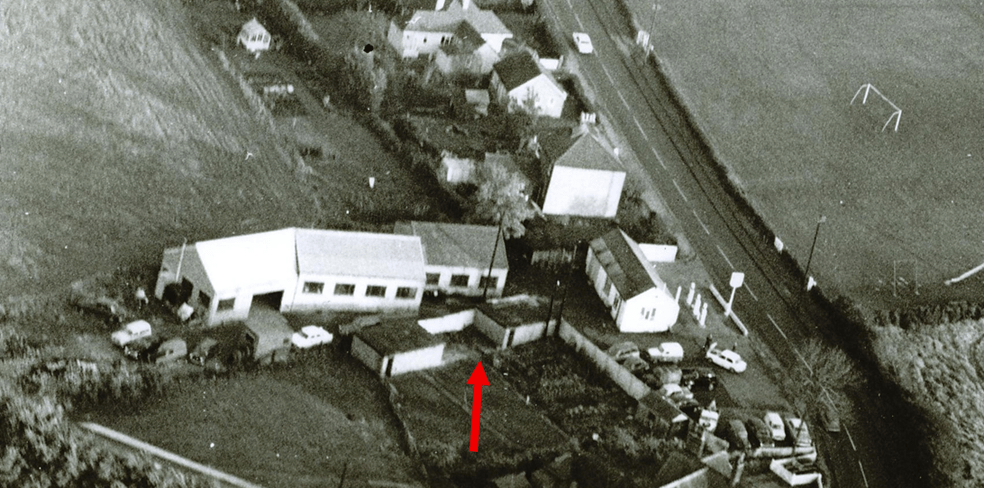

This aeriel photo of Bumbles Green clearly shows the two air raid shelters in the back of the headmaster’s garden as well as Welch’s Garage. It was probably taken around 1970

One shelter still stands in Old Nazeing Road, and is used as a garden shed.

Marcus and Gladys Hills celebrating 20 years at Nazeing County Primary School in 1958.

Gladys Hills was the wife of the village headmaster Marcus Hills. They lived in the school house at Bumbles Green. Gladys kept diaries of school activities as well as everyday activities. They are an interesting window into everyday life at the time. In January 1940 she fell in a ditch during a blackout; in February Marcus made barricades for the doors. In March Gladys made lists for the air raid shelter and for evacuation. These included ration books, bank books, medicines, baby bottles, bandages and colouring books for the children. They all wore name cards on elastic loops around their necks for 24 hours a day. It is difficult to imagine being a mother in these circumstances. Testimonies from those who were children at the time show that many accepted life as it was and just got on with it. Life could even be exciting for the children in the village during the war. Some were unaware of the anxieties of their parents.

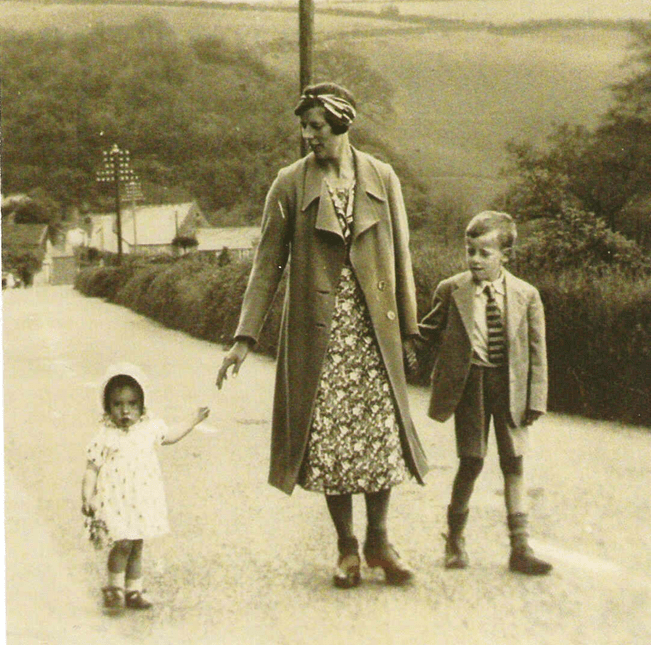

After Germany invaded Holland and Belgium and Italy entered the war in May 1940, Gladys and the children were evacuated to Devon, while Marcus remained at the school in Bumbles Green. He visited them during the school holidays. Her diary entries then mainly consisted of activities in the countryside in Devon, and the children’s illnesses. In February 1941 Gladys recorded frequently hearing the German planes flying over Devon to raid Swansea. On a more mundane level, she also records the sense of achievement at getting the children ready for bed before the blackout.

Gladys Hills in Devon with the family: 1941

In March 1941 Marcus told her that soldiers were in the school at Bumbles Green and there had been bad air raids. In May 1942, after many air raids in the south west Gladys returned to Nazeing with the children, and recorded her delight in cooking her first joint for 2 years as well as having a wash after 2 days without. July 28th, they could hear the guns in London. There were many air raids, and bombs dropped, all while coping with the children’s mumps and other childhood illnesses.

In October 1942 the family still went to the pictures at Hoddesdon to see Jungle Book, and there was a Ministry of Information film show at Chapel Hall in the afternoon of 8th October. Towards the end of the month there were air raids in the morning and the school children practiced going to the shelter. In December there were school parties (as usual) before the children broke up for Christmas. Every effort was made for life to continue as normal.

In 1943 more air raids were recorded. There were 48 fatalities at a school in Catford, London after it was hit. In February Gladys recorded that everyone went to: Another Film show by Ministry of Information at the Chapel Hall. During May – Wings for Victory Week – £186 was collected. This was a national savings scheme to get the community to sponsor aircraft.

Joyce Martin lived at 4 West View, Pecks Hill, she was 8 years old in 1939. She left her wartime memories on the BBC People’s war online project in 2003: The only shelter we had was to bring our beds downstair and if things were particularly scary, we dived under the stairs. Alternatively, we huddled under our heavy dining-room table. Later in the war, we were issued with a Morrison table shelter, a very heavy metal box with steel sides. It was never assembled, quietly turning bright orange in the garden till it was collected for disposal.

Apart from the fact that the sound of a propeller aircraft would wake me in the night, stomach in a knot for several years afterwards, my memories of the blitz are summed up by fear, noise and the conventional wisdom that if we heard a bomb whistle, it wasn’t for us, but if it was a whoosh, we dived for cover. (The whooshes luckily all landed with monotonous regularity on the unfortunate glasshouses 100 yards away). Pings and clunks from shrapnel on house and shed roofs gave the promise of more souvenirs to be gathered the next day, useful for possible swapsies for bits of downed Heinkel or Dornier. Robert Tubby said shell nose cones were the most prized acquisitions.

When Joyce was ten years old, she remembered waking in her parents’ double bed, to find her pregnant mother leaning over her with a pillow to protect her head, whispering: Please God, Please God and me saying It’s all right Mummy, I’ve had a lovely sleep. One casualty of The Blitz was the little village primary school which was sufficiently damaged for all the pupils — about 100 of us — to be sent to a local chapel hall where for a while we were all taught together in one room. My main recollection of that time is the amount of class singing we did: I’ve always been glad that I learnt so many songs from The National Song Book.

Bomb damage to the school may well have been the same occasion when Dennis Mead was returning home up the school hill towards Bumbles Green and threw himself into the ditch. He rushed home, to the sub- Post Office next door to the garage, expecting the worse, to find no one was hurt. The cat had been sitting in front of the fire and was badly singed from the down draft of the explosion.

Robert Tubby was 9 years old and lived with his family at Old Sun Cottage on Nazeing Common. The 1939 Register listed his father, Leslie Tubby, as a Shipping Clerk and ARP Warden. His sister, Felicia, was a few years older and recorded her memories in a letter to Robert many years ago: Sometimes there were daylight raids, but most often they were at night. Although Dad had built a reinforced concrete shelter onto the house, we never used it – Mum commandeered the bunks for keeping apples on!

We used to curl up in blankets either behind the couch or under an upturned armchair, in case a bomb should fall on the house. We would not, in theory, be crushed by falling rafters. Some nights they just emptied their bombs out as they crossed the fields, the craters left in the heavy Essex clay soon became intriguing mini ponds – frogs, newts, rushes etc.

Sometimes incidents took place after the all-clear was given, such as a dog fight, in daylight, one plane nose diving into front garden of Mr and Mrs Green’s cottage, setting alight the thatch. Dad rushed in for the hay rakes to pull the thatch off and save the house from complete ruin. It took days to dig the engine and remains out of the front garden.

This incident was actually two de Havilland Mosquito night fighter aircraft on patrol which were based at Hunsdon. They undertook an exercise in which one acted as the enemy and collided. One plane landed in the garden of Thatched Cottage, Common Road, Broadley Common. Both crew men died. The other crew successfully abandoned and parachuted to safety in Hertfordshire. Ref: North Weald Airfield Museum Archives – Crashes and Mishaps.

The Thatched Cottage, Broadley Common has just been re-thatched (June 2025), how many times has that happened since the repair after the crash 80 years ago?

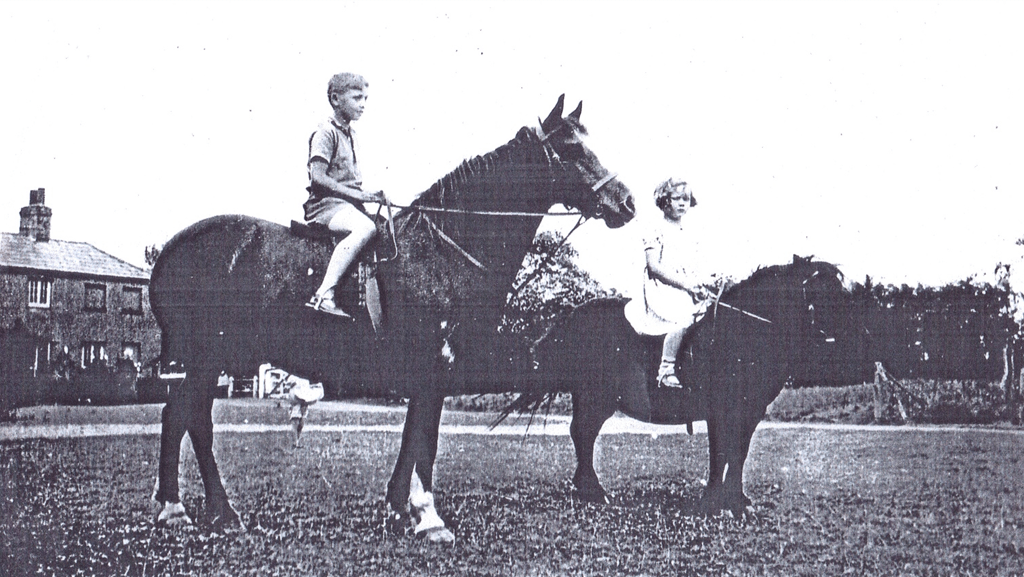

Rob Tubby and his sister on two ponies (Joyful and Granny) lent to them by Mrs Haycock of Broadley House, for the duration. This photo was taken outside the Sun Inn. Uppergate House can be seen in the background. There used to be a small pond on the side of the road as seen on the RHS of the photo.

Rob’s sister Felicia reported the following: Then there was the time when Alison, Mum and myself were coming back up the common hill. I was on the back seat of mum’s bike and she was pushing it up the hill, we heard the sound of a German plane – we dropped the bikes and ran for our lives across the ploughed field to fall in the ditch. It strafed the road and potato clamp alongside. It was the rockets I hated the most, the V1’s where mean and roaring – they always had something wrong with them – usually steering – one went round the village 3 times, each time getting lower and nearer the house. We stood transfixed on the lawn watching.

The one that really rocked the family was when the rocket exploded over the house – Dad was on watch in the yard and we were as usual sleeping on the sitting room floor – he fell in through the door saying “THIS IS IT!” the air went solid then shook and seemed to crack in pieces, then silence followed by a trickling sound, followed by crashing sounds – the tiles were rolling down the roof and into the yard – the poor old house had the shaking of its life – the plaster walls cracked the roof let in rain and Rob’s bedroom would be covered in bowls and buckets to catch the water. This was probably the last event recorded in the back pages of The History of Nazeing by the Rev. J Sutherland. March 19th 1945: Part of a Rocket Fell near the Sun Inn.

The Nursery Industry in Nazeing was targeted.

The nursery industry in Nazeing started to expand rapidly during the 1920s. Paynes Lane in Nazeing was one of the roads that had nurseries down the entire length of the road.

Joy Tizard’s father, Clifford Dick Chapman, built his first nursery, Langridge Nursery, on two acres of Langridge Farm land, owned by his father, George Chapman. He purchased part of Big Long Bean Mead for £112, and later he also bought another field, Linnets. Joy remembers part of the nursery being referred to as Linnets when she was a child, but didn’t realise until many years later that it was named after a field!

At the beginning of WW2, the nursery would have looked much like this. The wicker baskets you can see in the photo were phased out during the war, and replaced with cardboard boxes.

Langridge Nursery in Paynes Lane

Bomb damage at Nurseries

Between 1940 and September 1944 there were at least a dozen or so nurseries in Nazeing bombed. On September 13th 1940 seven high explosives were recorded in Nursery Road adjacent to the Aerodrome.

This photo shows some of the bomb damage at Langridge Nursery, damage at other nurseries would have been similar. On April 17th 1944 the records show one high explosive, plus 7 unexploded bombs. The photo below shows the damage as well as the height of the plants, probably tomatoes, at that time of year. Clifford’s diaries show that he planted out his tomatoes in February. The growing of cucumbers and flowers was discouraged so that more edible crops could be grown. Cucumbers were thought to have little nutritional value and were a luxury item.

Bomb damage at Langridge Nursery

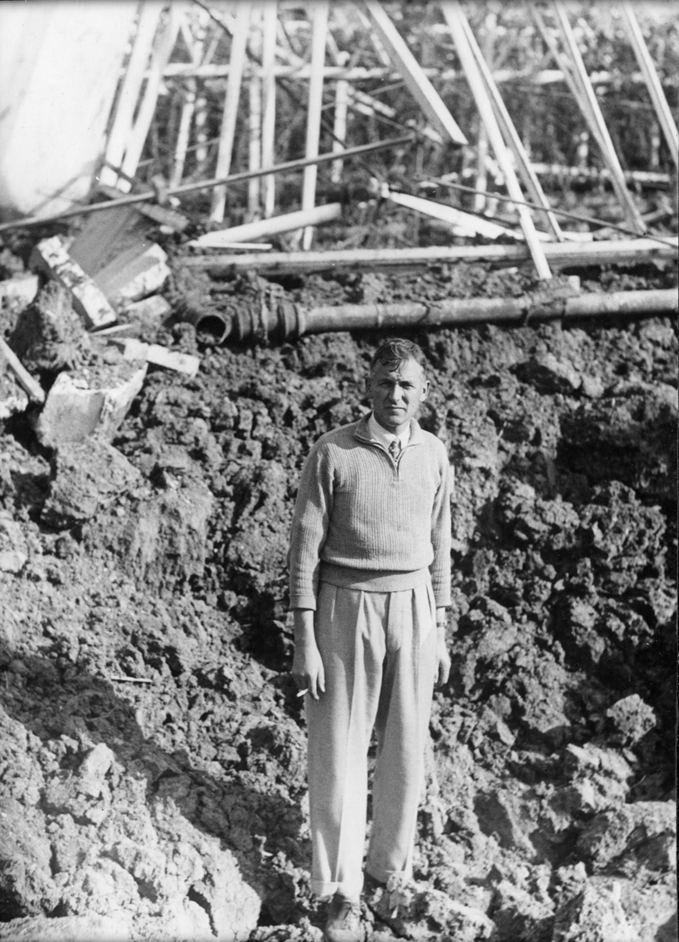

Clifford Dick Chapman amongst the ruins at his Langridge Nursery in April 1944

Because of the importance of producing food for Britain, growers were allowed petrol and oil for their vehicles and engines. Grace Harvey’s father Ted Tulley had his nursery (Tulley and Cowells) bombed in Hoe Lane. He always said the Germans were targeting the food industry, although some bombs were random. That pilots jettisoned their bombs before heading home. There were many more bombs on the nurseries in Nazeing than elsewhere in in the Lea Valley. Nazeing was and still is the most northern part of the Lea Valley Glass House Industry. General consensus is that the enemy bombers were harassed by the defence of London and would empty their pay load on the Nazeing glass houses as they returned home. We would like to hear from you if you have any information on this.

Joyce Martin’s house had views over the valley towards the river and the many glasshouses in Nursery Road. In the summer tomatoes were always in good supply. She would take some to school in Bishop’s Stortford and swap them for illicit farm-made butter. She recalled: I was woken by my mother calling, “Oh do come and look at these pretty flares!” Within seconds as I scrambled to the window they were followed by a Molotov bread-basket, a collection of incendiary bombs. The front garden at once became full of explosions and flames and on running to the back door, we found the back garden likewise full of fires. Fortunately, nothing landed on our house though many windows were broken. However, the next-door neighbour had an incendiary through the roof, through a bed where a Land Girl was asleep, then through the floor to the room below, then finally exploding under the floor. The neighbour Jack Willetts, had gone outside turning on the hose to deal with the fires in the garden. We heard his wife shouting “Jack, Jack, there’s one through the roof!” — and then a great shout of laughter. Turning round, he had caught his wife full in the chest with the stream from the hose! The Land Girl was unharmed, but the bed wouldn’t have offered much comfort afterwards!

We have two separate reports from later in the war, in September 1944, not of the bombs or rockets dropping, but of British troops heading for Europe.

Joyce Martin had one vivid snapshot of standing in the garden and trying to count as wave after wave of aircraft and gliders went over. They were going to Arnhem.

At the other end of the village, Robert Tubby’s sister, Felicia recalled the similar while standing at Harknet’s Gate, on Nazeing Common: The day we watched the planes towing long canvas gliders full of men – hedge hopping to get lift from the top of the hill, on their way to Holland – so many didn’t return.

Aeriel bombardment had caused much damage to the Nurseries, but surprisingly damage to buildings was limited. Many properties had damage to windows, tiles and plaster work. Casualties had been very small or non-existent.

The villagers managed to make sure life carried on as near to normal as possible throughout the war, with everyday activities shaping people’s lives – until 12th November 1944. We will tell you about the day that changed life in the village for ever in our next blog.